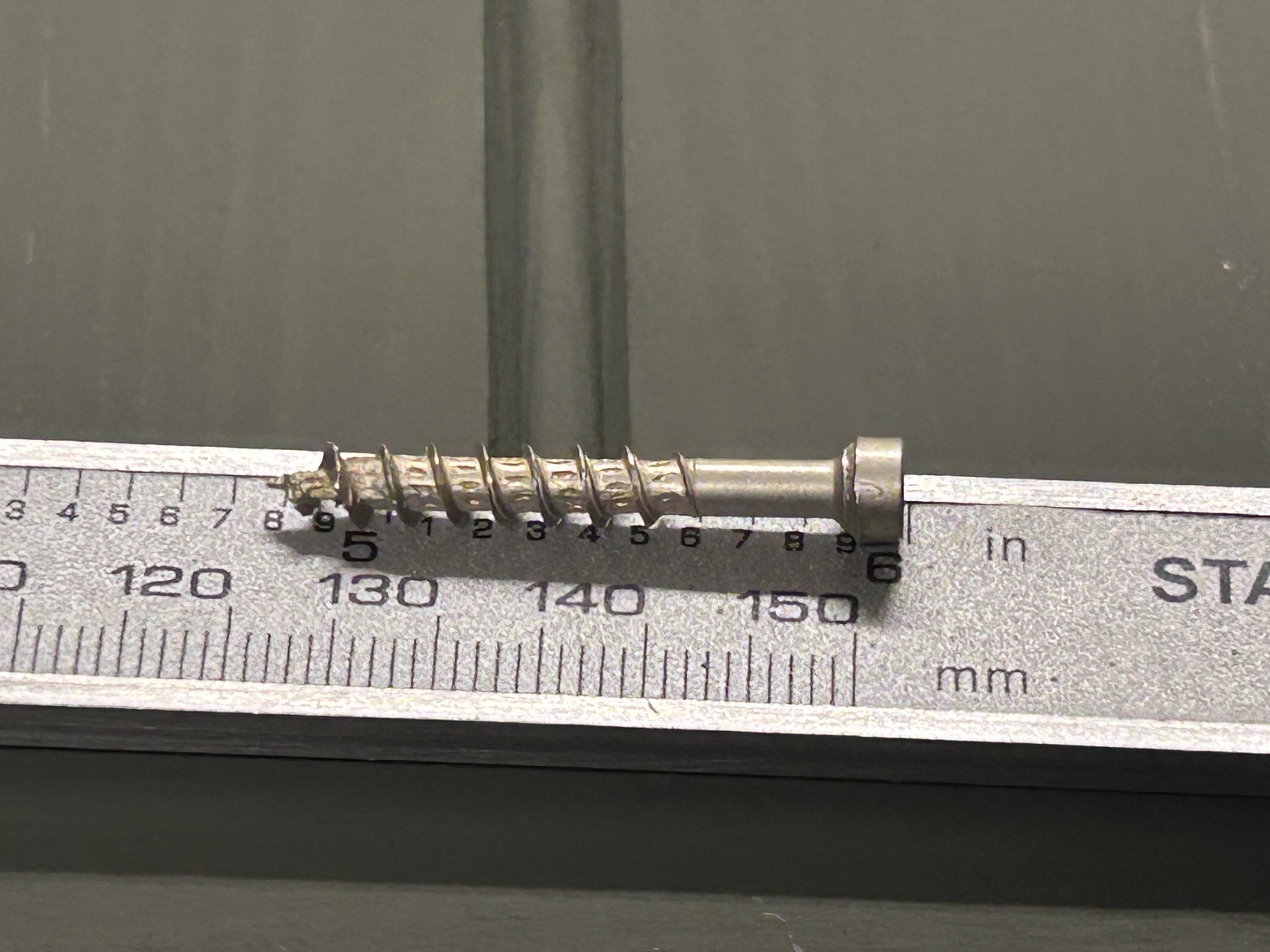

1¼" SPAX Power Trim Screws on 1x2 Legs

Customer damage reports showed that the legs take most of the abuse during shipping and drops. This test evaluates switching from brad-nail + glue legs to brad + 1¼" SPAX Power Trim screws installed on a diagonal pattern (two per leg).

Full test notes

Objective

Confirm that adding 1¼" SPAX Power Trim screws to the leg attachment dramatically reduces leg failures (legs cracking off, pulling away, or loosening) during shipping and field use.

Method

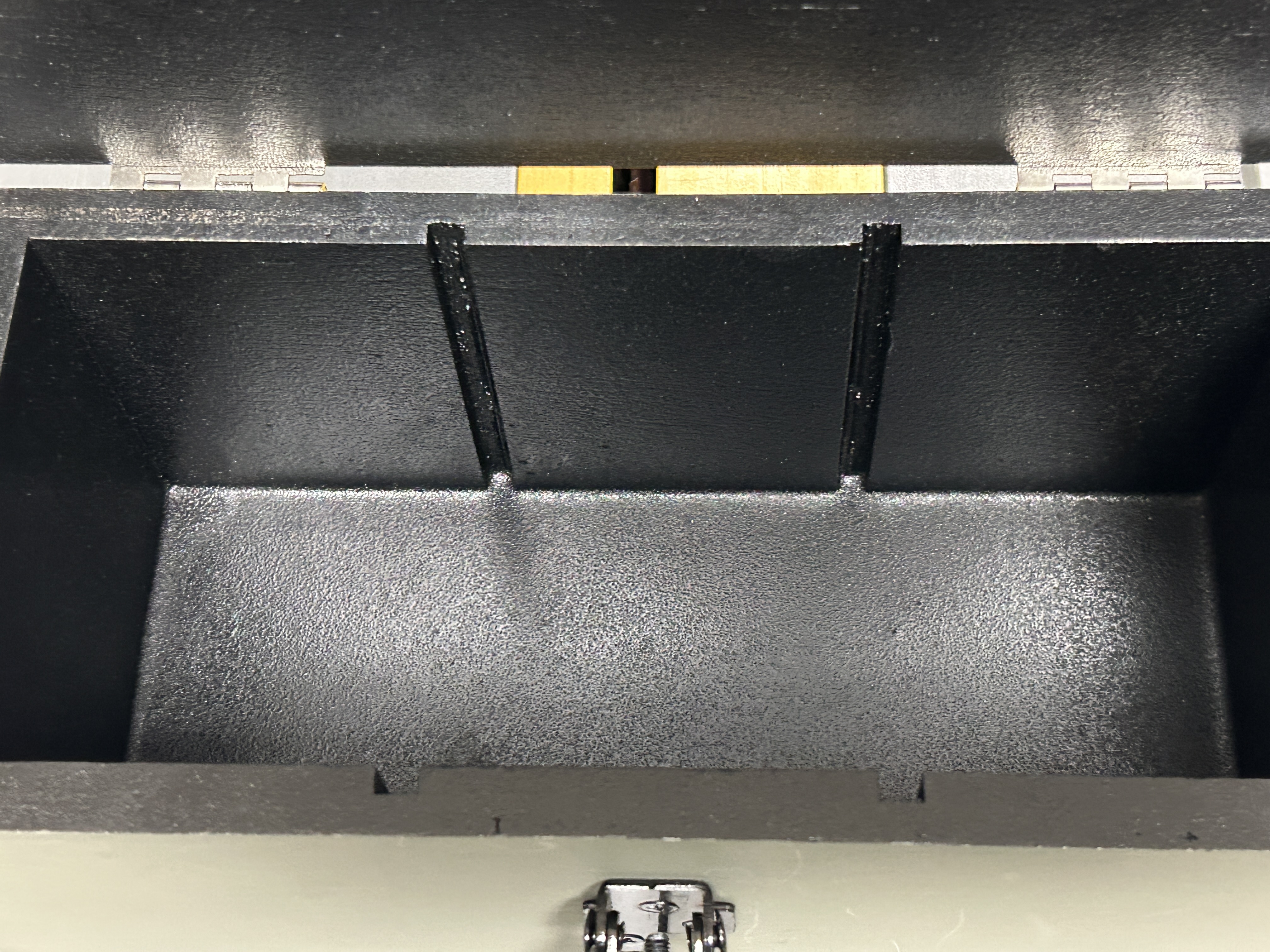

- Apply glue + brad nails as usual for leg installation.

- Add two 1¼" SPAX Power Trim screws per leg, installed on a diagonal (caddy-corner) pattern – one high, one low.

- Repeat on all four legs for each test box.

- Send multiple boxes through standard carriers and monitor any damage reports.

Key Observations (so far)

- Legs appear to be acting as sacrificial impact structures – they take the brunt of abuse when boxes are dropped or slammed.

- With screws + glue + brads, legs feel much more rigid in tension and shear. The wood itself can still crush if severely pinched, but the legs are far less likely to separate from the box body.

- Early shipments suggest a reduction in leg-related failure claims compared to glue + brads alone.

These boxes are currently designed so that stacked units rest on the tops of the legs rather than on the lid rails. I originally built them this way to prevent the lids from getting scratched, gouged, or scuffed when boxes are stacked during use or transport. The taller legs protect the lid finish — but this also means the upper box has less surface area to rest on, which reduces overall stacking stability. A future improvement could involve designing a groove, notch, or interlocking feature on the tops (and possibly bottoms) of the legs so stacked boxes positively locate into each other. This would keep the lids protected while greatly improving stability. Alternatively, if a field-use variant is ever developed, we may revisit the idea of allowing the upper box to rest directly on the lid rails for maximum footprint and stability.

Preliminary Conclusion

For all designs using 1x2 solid-pine legs, 1¼" SPAX Power Trim screws are now considered a standard structural requirement, not an optional upgrade. This will be refined as more data and photos are collected from the field.